Blog

How Can an Understanding of Masculinity Help in Tackling the HIV Risk Faced by Both Men and Women?

Written by Hannah Fitzgerald

August 1, 2017

How are women’s HIV risk factors understood?

It is now widely recognised by the United Nations, World Bank and other international organisations that women have been disproportionately affected by HIV/ AIDS in low and middle income countries. For instance, figures from Kenya show a considerable difference between the proportion of men and women affected, with prevalence rates of 7% for women compared to 4.7% for men in 2015.[ii]

With the situation in Kenya being reflective of a broader gender imbalance across much of sub-Saharan Africa, it is unsurprising that the discourse around tackling HIV/ AIDS focuses largely on women and their vulnerabilities. However, this approach of focusing on women has, as yet, done little to challenge or even to understand the behaviour of men.

Men’s behaviour is too often written off as selfish, dangerous and inflexible. Such an approach discounts the fact that men’s behaviour has a crucial role to play in stemming the tide of both women’s and men’s vulnerability to HIV/ AIDS.

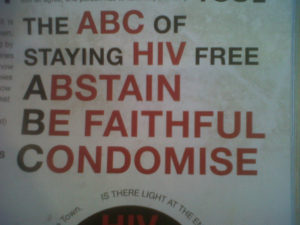

Image from US Army Africa Photo Library, Flickr, taken in Kisumu, Kenya on 25 April 2010. No changes were made. [iii]

What are the limitations of focusing solely on women’s behaviour?

There are undoubtedly some practical advantages to employing a simplistic focus on women alone, as such as focus has successfully attracted both funding and international attention. However, this approach has done little to disrupt the gender binaries which continue to dominate approaches to tackling HIV.

Such binaries include the idea of women as victims, men as attackers, women as powerless and men as powerful. While these binaries do, naturally, stem from lived realities in many instances, they do little to examine the underlying social issues at play and they offer little in terms of long term behavioural change, which is crucial to preventing the further spread of HIV.

Furthermore, focusing solely on women’s vulnerability can deny the very women who are targeted by these programmes much needed recognition and understanding. Such programmes are quick to write off women in low and middle income countries as lacking agency. As Desmond Cohen and Elizabeth Reid argued in their paper questioning the use of women’s vulnerability as a concept for health programming, programmes which use such a concept have ‘often closed out possibilities for social change and, in doing so, have disempowered those who most need our understanding and support.’[iv]

Additionally, a number of funds and programmes with a sole focus on women have promoted policies which are not necessarily accessible methods of protection for women. Encouraging commercial sex workers to tell their clients to wear condoms, and discouraging young women from entering into transactional relationships with older men may appear logical responses in the fight against HIV.

However, they overlook the fact that women are in many cases driven to such relationships by their exclusion from alternative livelihood prospects. As such, policies based solely on women’s behaviour, and those which assume that behaviour is formed at the individual, rather than the societal level, do not provide appropriate ways of negotiating sexual risk for young women and girls. If behavioural change in the long term is to be achieved, it is important to not only target changes in women’s behaviour, but to work with both women and men.

Why examine masculinities?

Just as expectations of women differ depending on the context, masculine expectations are also varied. There are, however, some strands of masculine expectation which run through different countries and communities, notably the breadwinner role. While men in developed countries have tended to be able to secure access to breadwinning as a marker of their masculinity, men in low and middle income countries, in particular those in rural areas of countries with limited formal economies have found their access to masculinity through breadwinning is fragile.

To take one example from East Africa which reflects broader struggles in accessing livelihoods, fishing communities around Lake Victoria have witnessed particularly high rates of HIV as men, threatened by their inability to provide financially due to declining resources in the area have begun to engage in relationships with a number of women in an attempt to reassert their masculinity.[v] Such practices have resulted in a difference of 13.8% between the HIV prevalence rates in the lakeside region of Kisumu compared to the capital Nairobi.[vi]

Fishermen on the banks of Lake Victoria

In addition to the masculine expectation of the breadwinning role, meeting masculine expectations requires men to play a limited role in family planning and instead, men are expected to be sexually virile, and express no concern for the spacing or number of their female partner’s pregnancies. To be clear, this should not imply that individual men have no concern for the reproductive health of their partners, simply that this behaviour does not fit with the masculine expectation of sexual virility and as such men may struggle to express such sentiments.

Sexual assertiveness including actions such as refusing to wear a condom and engaging in sexual relations with multiple partners puts both men and women in a position of extreme vulnerability in terms of HIV.

As such, while it remains important for HIV intervention programmes to examine women’s vulnerability, this cannot be done without an understanding of why men perform in certain ways. While there are multiple forms of masculinity at play within all communities, in general, men are expected to exhibit physical strength and assertiveness in their relations with women and younger men and they are discouraged from showing physical weaknesses and appealing for help or advice.

While these markers of masculinity are in many regards the sources of men’s stronger position relative to women, they also make both men and women vulnerable in terms of HIV.

What now?

It is now time for the expectations attached to masculinity to be recognised more fully by those working in HIV prevention, and incorporated into a greater number of programmes and policies. We must employ a bottom up approach, looking first at what masculine expectations are and then at why men are increasingly failing to meet them, and how this failure triggers risky sexual behaviour which increases HIV-related vulnerability.

Organisations have in some cases begun to do this, with one such organisation, Stepping Stones, asking communities to examine the relations that occur between men and women not only sexually but also socially. By shifting the focus from individual actions to society wide gender relations, the programme has been able to bring about longer term behavioural change.

Stepping Stones intervention manual ‘Working with Men and Boys’, indicating how workshops with men can encourage communication about their concerns and the pressures they face[vii]

Rather than looking solely at biological factors, and telling a simplistic narrative of men as sexual aggressors and women as defenceless victims, we need to uncover why men feel pressured to pursue sexually risky behaviour, and why their access to traditional forms of masculinity has been threatened. Understanding this in the context of low and middle income countries requires understanding livelihood access, and accompanying HIV prevention programmes with livelihood programmes.

Only by doing this can HIV prevention programmes make themselves appropriate to their surroundings, and help both men and women to navigate the gendered pressures which increase their risk of transmission.

[i] Kenyan National Aids Control Council Country Profile 2016

[ii] US Army Africa Flickr image

[iv] IRIN News video about Lake Victoria’s declining resources

[v] Kenyan National Aids Control Council Country Profile 2016

[vi] Stepping Stones intervention manual ‘Working with Men and Boys’

Hannah Fitzgerald is a Development Studies MSc student at SOAS.