Blog

Why Don’t People Use Mental Health Services in India?

Written by Tessa Roberts

July 30, 2018

Mental health is a growing concern in high-income countries, but has long been neglected in development work. That is now slowly beginning to change as we increasingly recognise the links between mental and physical health, and as suicide overtakes many traditional killers as a leading cause of death in young people.

The World Health Organisation recommends increasing access to treatment by delivering mental health services through primary care. Yet implementing this in practice has proven far easier said than done.

The DfID-funded Programme to Improve Mental Health Care (PRIME) studied this strategy in five countries, including India, where only 14% of people with depression seek treatment even once it’s available through primary care. We aimed to understand why so few people seek care for depression, and what we can learn from this for other low-resource settings.

A Community Health Centre in Sehore sub-district, Madhya Pradesh

Just a matter of geography?

Sehore sub-district, the PRIME site, is in Madhya Pradesh, one of the poorest states in India. Public transport is limited, and only 1 in 4 households owns a vehicle.

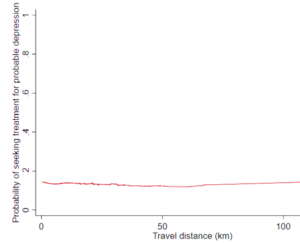

We calculated travel distance from each household to the nearest public facility offering depression treatment, before and after PRIME. The average distance was over 30km before integration, but still over 10km afterwards, so one explanation for limited help-seeking is that people simply can’t get to services.

However, we were surprised to find that people living right next to services were just as unlikely to seek treatment as those living 20km or more away.

If geography isn’t to blame, then what is? We interviewed people who screened positive for depression and their relatives who brought up three key themes.

1. Low severity

Perhaps unsurprisingly, participants made treatment decisions based on the severity of symptoms.

Depressive symptoms exist on a continuum, from mild distress to cripplingly low mood, and many people who meet diagnostic criteria have mild symptoms.

Although public services are free, attending means losing wages, due to long waiting times and restricted opening hours. Families will borrow money and vehicles, but only when a healthcare need is urgent.

2. Causes not addressed

People spoke of their experiences in terms of stress, or “tension”, due to poverty and financial pressures, bereavement, marital problems or domestic abuse. Many also described suffering from multiple “physical” health problems.

“Money is the issue. We have no money in our home.

If I had money then all of my tension would be ended.”

Participants described needing financial protection, better working conditions, affordable education for their children, social support, and the ability to retire. They also wanted effective general health care to treat what they saw as their primary conditions. Many believed that if these needs were met, they would no longer feel depressed.

3. Mistrust of public health services

Interviewees reported negative experiences of public services, and said government health workers lack the time or motivation to provide quality care, unless bribed. Most people therefore consulted private providers rather than using the facilities where mental health services were available.

A sign for the “Mann Kaksh” (mental health room) in a Community Health Centre

So what do these findings mean for public health and development priorities?

Recommendation 1: Strengthen health systems

Poor quality care and a lack of accountability are major problems in the Indian health system, where average consultation times are as low as two minutes. People must trust public services before they begin to use them. This means investing in improving the quality of services – and not only for mental health.

The private sector is currently the main source of care. Engaging with this sector in the meantime is essential to ensure that, at minimum, they aren’t providing harmful treatment or charging low-income families for ineffective care.

Recommendation 2: Community dialogue is essential

Many blame the lack of demand for mental health services on “low mental health literacy”. This leads to calls to educate communities.

However, research on the social determinants of mental health shows that the causes that participants described are important risk factors for depression. Rather than trying to change participants’ perceived needs to match the services offered, we would arguably do better to listen and adapt our interventions accordingly. This may mean going beyond health facilities, and engaging with the social and economic conditions that cause distress.

Recommendation 3: Prioritise quality over quantity

Low treatment-seeking rates arise from lack of demand more than lack of supply. Those who seek treatment tend to have the most severe problems, for whom mental health treatment is most beneficial. However, the quality of care received by most who seek it is abysmally low.

We found that people are willing to travel for effective treatment. Providing good quality care would build trust in the system, thereby increasing demand. What’s more, many with mild depression would benefit more from social work interventions than from formal mental health treatment.

Our key recommendation? Providing good quality, holistic health care for those who do seek help may do more good than having everyone who meets criteria for depression seek treatment.

Tessa Roberts is a PhD student at the Centre for Global Mental Health, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, where she is funded by the Bloomsbury Colleges. She also works at the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience, King’s College London, where she coordinates an MRC-funded international research programme on psychotic disorders, entitled INTREPID II.