Blog

Private lending and debt risks of low-income developing countries

Written by Christina Laskaridis (SOAS), Bruno Bonizzi (University of Hertfordshire) and Jesse Griffiths (The Finance Innovation Lab)

June 29, 2020

Low-income developing countries (LIDCs) are greatly affected by the coronavirus pandemic, and sovereign debt has become a major concern. While the current situation is unprecedented, concerns about the potential for debt problems in LIDCs have been mounting in recent years.

Our new ODI report provides timely insights into the risks that the wave of sovereign bond issuances may bring for LIDCs. Our report examines the 16 countries in the LIDC group that have been at the forefront of this new wave of borrowing from the private sector. We analysed 57 international bond issuances, worth $52 billion, made by these 16 countries between 2010 and 2019. We examine the extent to which risks associated with the cost and availability of this kind of finance were driven by global financial and economic conditions and identified additional future risks that should be considered in the current situation.

Our study builds on the concept that the cost of borrowing and risk of refinancing are primarily not only determined by conditions in the borrowing countries. Rather, the emergent financial integration of some developing countries into global financial markets exposes them to common dynamics of the global financial system. This can be captured by the notion of ‘global liquidity’, which can be defined as the ‘ease of international financing in the international financial system’ (explained more here) This changing availability of international financing has become a key driver of the debt dynamics of developing countries (UNCTAD 2019). These issues stand at odds with the emphasis on domestic mismanagement and fiscal deficits as the cause of looming debt vulnerabilities. It therefore suggests that concomitant policy responses that rely on domestic contraction, fiscal consolidation and domestic structural reforms are misplaced and harmful – for many reasons – including that they do not tackle key drivers of the problem.

In our study, we find overall support for our contention that global liquidity is a key driver of issuance and borrowing costs. Issuances follow the patterns of global financial conditions – with most bond issuances happening during four periods (shaded areas below), which coincide with periods when liquidity was loosening. Furthermore, the cost of borrowing is correlated with global financial conditions, so that when global finance is hard to access, there is less ‘liquidity’ – and borrowing costs rise for LIDCs. Conversely, LIDCs have, understandingly, tapped into global markets when costs of borrowings were low, in historical terms. Despite this however, the cost of borrowing for LIDCs remains very high, with an average interest rate of more than 7%, and as high as 10.75% in one instance.

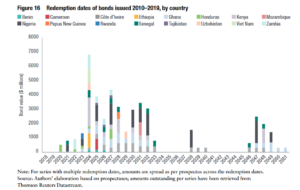

With the ongoing global crisis, there are major minefields on the road ahead as LIDCs need to refinance existing bonds. In 2020 and 2021, major repayments are due in Honduras and Senegal, and refinancing needs are set to rise significantly with a major spike in 2024. This will be particularly problematic for countries such as Côte d’Ivoire, Senegal and Zambia whose external outstanding bonds exceed 12% of GDP. The tightening of global liquidity conditions will be a major challenge to those countries which hoped to refinance through global markets at inexpensive rates.

In these conditions, debt relief is necessarily back on the agenda. However, the existing creditor-centred approach to dealing with debt repayment difficulties will bring unequal and unfair consequences for developing countries. This had led once again to the call for a statutory, neutral and overarching approach resolving debt crisis based on impartial assessments of a country’s debt situation.

We note several legal characteristics of the bonds that may make them difficult to restructure:

- Legal jurisdiction: Of the 55 contracts studied, 49 were made under English law, and the remaining six under New York state law. Use of foreign law means that in the event of a dispute, courts are more likely to uphold creditors’ rights.

- The pari passu clause: The bond issuances contain modifications to the pari passu clause that had been interpreted by some courts to mean that all creditors should be repaid even if a restructuring had taken place, giving power to ‘holdout’ creditors. Three of the bonds issued during this period contained the pari passu wording that was successfully used by holdouts.

- A quarter of bonds issued contain majority action clauses (CACs) which allow creditors more power to block restructuring, while the majority – 71% – now contain the most recent generation of CACs that are designed to prevent creditors in one bond series from blocking broader restructuring.

Our report concludes that the steps taken by the IMF and G20 to provide limited debt service relief and rescheduling will not be enough given the scale of the crisis being faced. Without comprehensive inclusion of private creditors, this relief will be redirected to the substantial upcoming payments countries have to pay to private creditors, including for bond servicing and redemptions. This paper’s findings highlight the need for immediate standstills on all debt payments, to make resources available for addressing the pandemic. This must be followed by a more comprehensive approach towards restructuring and cancellation. The report give impetus to the creation of effective debt work-out mechanisms for countries in crisis, to restructure with all debts simultaneously in a fair and rapid manner.

Over the medium run, it is important to fully appreciate the procyclical nature of global liquidity in determining debt dynamics and sustainability, as market borrowing becomes ever more prominent in LIDCs. These dynamics are highly asymmetric: global liquidity is a major determinant of borrowing conditions, but LIDCs themselves have little control over it. This is a structural issue and it is therefore paramount that more sustainable and stable sources of long-term finance are put in place, if we are to avoid major debt crises.

About the authors

Christina Laskaridis is a PhD Candidate (SOAS University) and incoming lecturer in Economics (Open University)

Bruno Bonizzi is Senior Lecturer in Finance at the University of Hertfordshire, Business School

Jesse Griffiths is CEO at the Finance Innovation Lab