Blog

Grassroots initiatives promoting literacy and literature in Luganda: A case study from Uganda

Written by Zaahida Mariam Nabagereka

August 29, 2018

According to the Global Partnership for Education, East African country, Uganda’s education system is hampered by problems including the inadequate availability of education materials and high rates of student and teacher absenteeism. What’s more, Prof. Abdu Kasozi, former Executive Director of the National Council for Higher Education, recently criticised the country for its ‘poor reading culture’. Author, Waalabyeki Magoba, provides a great example of using children’s literature to promote literacy at a grassroots level in Uganda.

Background

Uganda has a population of approximately 39 million people, 80% of whom live in rural area. In 1894, it joined the British Empire, whose istrators ruled indirectly through the Baganda, the largest ethnic group in the region. As a result, this substantially influenced Uganda’s linguistic landscape. While there are around 41 languages in Uganda, the two non-indigenous languages, English and Kiswahili, are the country’s official languages. What’s more, government istrators, educators and business leaders use English.

Luganda is the largest indigenous language, with over 5 million people who speak it as their native language. Furthermore it is the main indigenous language for wider communication. However it’s important to remember that no indigenous language has official or even national status. This raises significant questions regarding the perceived importance of indigenous Ugandan languages. It also throws into question the day to day reality of their uses, which far outweighs that of English or Kiswahili.

In 1969, Ugandan academic Taban Lo Liyong infamously dubbed Uganda a “literary desert”. Despite this unflattering portrayal, literary production has blossomed in Uganda in the past few years. Okot p’Bitek, Doreen Baingana, Timothy Wangusa and Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi are just some of Uganda’s many nationally and internationally celebrated authors. I believe that key literary institutions, Makerere University Literature Department, Fountain Publishers and FEMRITE, a NFP publisher, have largely contributed to Uganda’s literary flowering. However, English remains the main language used in literature, as this is where there is a substantial market. Additionally, the country’s language and education policies have fostered the growth of the English literature market.

Literacy in Uganda

Uganda’s current education policy stipulates that one of 35 approved local languages will be the medium of instruction (MOI) for the first three years of primary school. In the fourth year, the MOI changes to English which had previously been taught as a subject. Although this is a worthy policy, its implementation has been unsuccessful. As a result, students have low rates of literacy in English as well as the country’s indigenous languages.

Luganda literature at a grassroots level

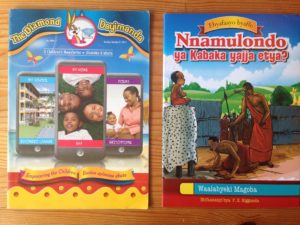

Author, Walabyeki Magoba, has been writing for children since 1994 to address Uganda’s poor reading culture. His first books include a Luganda translation of Aesop’s fables. Magoba also writes more traditional Kiganda stories, which he remembers from his youth. His most popular books focus on the genealogy of Buganda’s clan system and detail the exploits of Kintu, the kingdom’s legendary founder.

One of Magoba’s most popular texts is a short bilingual novella about a girl called Talantina. It’s a didactic story that encourages youngsters to stay in school, take pride in themselves and their education. In 2014, Magoba began a children’s newsletter, which invites children from schools the author has visited to send in a short piece of writing on any subject. These pieces can be in English or Luganda. When Magoba and his team compile the newsletter, they translate each text so they appear in both languages.

Ekyoto

Since 1999, Magoba has hosted Ekyoto radio show on CBS Radio station, one of the most popular Luganda language stations in Kampala. It’s a cultural show aimed at a family audience with language games that are fun for all ages. Once a month, Magoba and his team invite a school to perform live on the show. Performances include excerpts of plays, poems, songs or well known Kiganda stories.

Literacy and literature Festivals

Magoba established literacy and literature festivals in 2014 to encourage kids and schools to enjoy reading in Luganda. In October 2016, the largest festival took place in Kamuli, Wakiso District, which is also his home village. It’s a fun day that involves different literacy-based activities such as spelling quizzes, reading aloud and drama performances. All activities are based on the Luganda story books he writes.

For Magoba, it’s pivotal that he engages the support of teachers and parents who want children to gain literacy in their first language, Luganda. While children are the main readers of his books, headmasters and parents are the gatekeepers to his audience. By default, they also become his audience.

Although Luganda has neither official nor national status as the largest indigenous language, it has not deterred literary activity. Rather, ambitious authors are using innovative methods to reach their audiences.

Zaahida Mariam Nabagereka is a third year doctoral researcher at the School of Oriental and African Studies who is studying literature production in Uganda. Her research looks at the relationship between texts in Luganda, the largest indigenous language in the country, and texts in English. She also holds a Bloomsbury studentship.